- Home |

- Search Results |

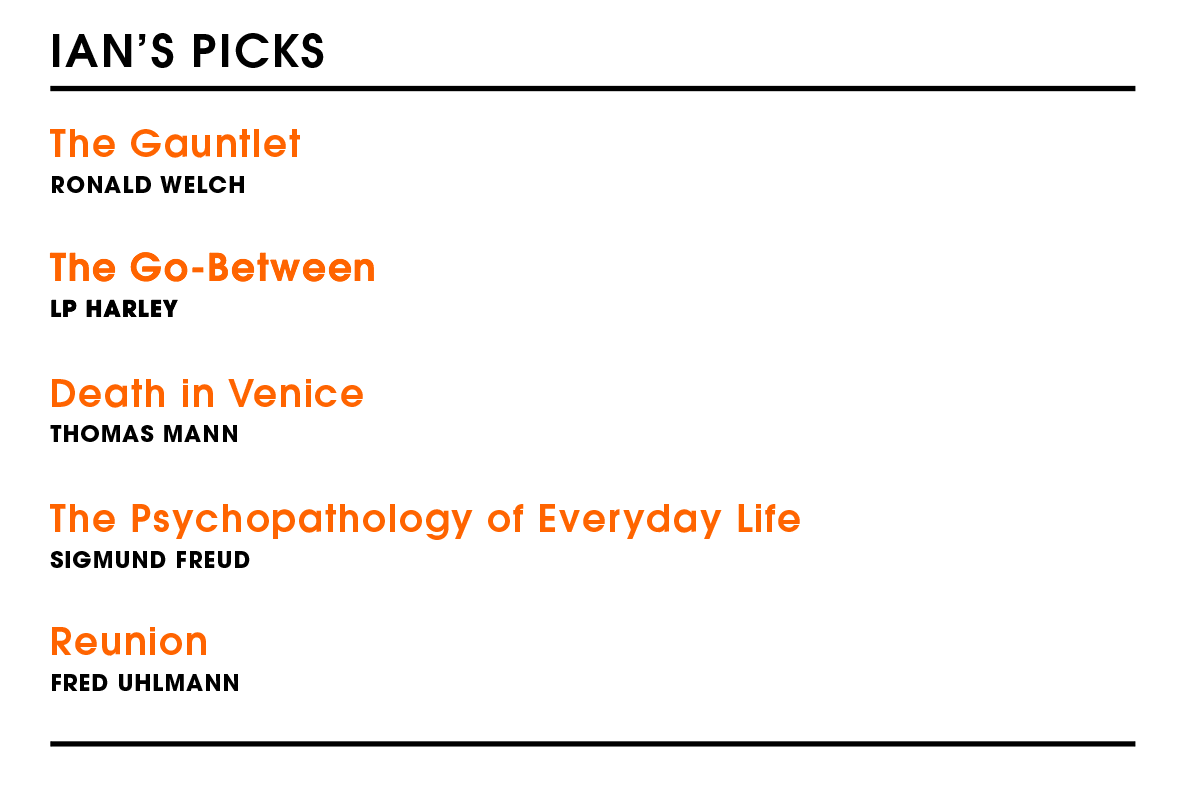

- Shelf Life: Ian McEwan

Shelf Life: Ian McEwan

To mark his new satirical novella The Cockroach, British author Ian McEwan shares five books that have shaped his life, from a childhood spent in North Africa to his first flushes of literary fame to Freud, whose 'ghost stalked my earliest stories'.

When I was eight years old I was in hospital having a sinus operation. The nurse wheeled in a book trolley, and I plucked a copy of The Gauntlet by Ronald Welch (1951) off the shelf. It’s the story of a boy in Wales who comes across this rusty gauntlet, slips his hand in and suddenly find himself in the 13th century - and boy, did I want to be in the 13th century at that point. He becomes a young prince and there’s lots of falconry and he makes passionate friendships.

Then, right at the end, he takes the glove off and he’s back lying in the grass and he realises the bones of those people he met are now crumbling to dust in a nearby church graveyard. For me, it was quite a savage moment, the thought that the bones of my parents and all the people I loved - and my bones, more to the point - would one day go the same way. It was one of my first premonitions of mortality, which I guess we get all along the way in life.

I read it in a day, and when the nurse came around with the trolley again I looked at all the other books and thought: I only want this one. So I read it again. And I suppose I spent the rest of my life hoping one day, I’d write a book that would cause someone else to do the same. Being reread is the highest praise for an author, I think.

‘Being reread is the highest praise’

I didn’t enjoy boarding school at first. I was 11 years old and 2000 miles from home and rather inarticulate about emotions. I wasn’t tearful, I just sort of closed down. It was full of very streetwise, bright, working-class London kids so I got my tastes from them and became a Chuck Berry fan. Then, somewhat later, an English teacher took me aside and told me I was clever, which was an extraordinary piece of news.

I left school feeling the study of literature was a sort of priesthood for which I was now going to have to devote my entire life, and I was rather unbearably contemptuous of people who didn’t know their way around things like The Waste Land. What on earth were they doing with their lives?! I was completely foolish. But within a very short time at university at Sussex I became more humble. Death in Venice by Thomas Mann (1912), which was one of my first confrontations with European literature, played an important role in that.

‘It was the first time I began to feel like a writer’

It’s the story of an elderly writer who goes to Venice at a time when there is a cholera outbreak, falls in love with a boy from an aristocratic family and vaguely pursues him without actually confronting him. It’s a very beautiful novella, not only about death but about a writer and his subject, an unspoken love and a reckoning. I was 20 years old, and it had a big effect on me. It was symphonic, it was grand... the scale of it stretched far beyond the narrow confines of a short novel. I was about to start writing fiction and suddenly I had, not something to imitate, but an elated sense of what could be achieved.

My first moment of real validation as a writer came a few years later. I started to place my short stories in a literary publication called America Review, edited in New York. One morning there was a thunk on the carpet floor and it was a brown envelope with the latest copy inside. I remember it so distinctly: it was bright pink. And in white letters, all in the same size, it said: ‘Gunter Grass, Susan Sontag, Philip Roth, Ian McEwan’. That was an amazing moment. I’d read and admired all those authors. And now I could at least think about beginning to call myself a writer, something I hadn’t dared do at that point.

Around that time I read Freud’s The Psychopathology of Everyday Life (1901). It beguiled me, the idea of an unconscious that had symbolic qualities and narratives that could yield meaning. Later on, I became a sceptic about him - especially his construction of dreams and his notions, which now seem rather repellent, about infantile sexuality - but at the time I thought: ‘I can do some dangerous and dark things with this’. Certainly the ghost of Freud stalked through all of my early stories.

Success came to me young, with my very first volume. It was everywhere. It was notorious. People either loved the stories, or hated them. It was delicious. There’d be some old fogies on the TV saying ‘this is absolutely outrageous, this is disgusting’ and I’d think: ‘yes!’. I was fine with it. I was 26 years old, just two years into my friendship with Martin [Amis] and Hitch [Christopher Hitchens]. We were running around town having a lot of fun; the new kids on the block.

‘Freud stalked my early stories’

Literary fame is nothing like football or movie fame. It was never oppressive. There was no internet, so publishing was still a rather dusty and gentlemanly affair. Nobody asked about sales. Advances were minimal, but you could get by on journalism. Rents were very low, which is where I feel younger writers are at a huge disadvantage. I could write a piece for the Radio Times or get a story in the American Review and not worry about money for 2-3 months. There were no machines to buy. If you had three pairs of jeans and a t-shirt and a couple of shirts and one terrible suit, that was all you needed. The rest was food and drink and books.

These days, I discover new books mainly by trusted friends recommending them to me. That’s how I came across Reunion by Fred Uhlmann (1971) about a year ago. It’s a novella about a Jewish boy at German school in the early 30s who befriends a charismatic boy from a rather high born family. They have a very powerful, sort of homoerotic love affair, but slowly the parents of this second boy intervene.

It’s about something that’s always fascinated me: how huge stirrings in the geopolitical world can radically transform intimate, private relationships. Also, the whole novel turns on a sixpence on the very last word. It lands in a very unforced way and it just takes your breath away.

I like to preserve the mornings for writing and read in the afternoon, although if something is really going well, I’ll persist. I love airplanes. I’ve realised it is about the only place left where the internet can’t get you. So if I have to go to New York I think great: five hours of reading plus dinner! Reading a novel is much like life in that you forget most of it. Often we carry around not the memory of a book itself but our opinion of it. So rereading is crucial.

Ian McEwan's new novel The Cockroach publishes 27th September 2019.