- Home |

- Search Results |

- The power of fables: the authors of Pig Wrestling on how simple stories can change your life

The power of fables: the authors of Pig Wrestling on how simple stories can change your life

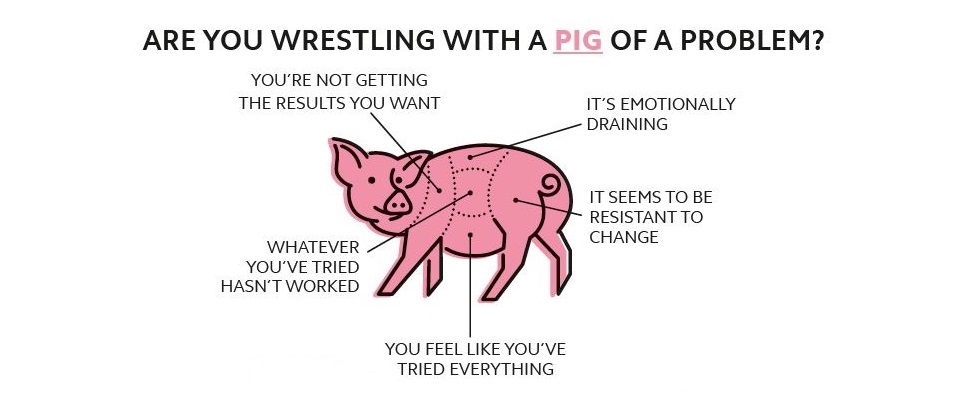

Fables carry a certain magic. In psychology, fables are a powerful tool to convey complex ideas in a simple package. Pete Lindsay and Mark Bawden, the authors of Pig Wrestling, discuss the magic of fables and how their ‘pig wrestling’ method can help you overcome any interpersonal problem, whether at work or in your personal life.

Why choose the term ‘pig wrestling’?

Mark: It might seem like a bizarre concept at first. As psychologists we do a lot of talks on problem solving and what to do when you find yourself stuck. But the clinical nature of these talks causes them to not be particularly sticky. During a coffee break at one of our talks someone came up to us and said it had reminded them of a George Bernard Shaw quote, ‘I learned long ago, never to wrestle with a pig. You get dirty, and besides, the pig likes it’. Everyone laughed, because that’s exactly how it feels. We thought it would be a great metaphor to capture what we’re trying to describe.

Pete: It’s a simple metaphor that everyone seems to intuitively connect with. It’s that feeling of being overwhelmed by a problem and being unable to get a handle on it, no matter what you try.

Why did you choose a fable to explain this concept?

Pete: We’ve read a lot of business and psychology books, and one of the things we loved about fables is that they’re so accessible. They take a complex message and, relatively indirectly, convey it to the reader. The reader is engaged with the story, but under the surface they are learning something quite powerful. Human beings are natural storytellers, so we wanted to craft something that would be easy to absorb without the complexity being obvious.

Mark: There is a danger to writing fables though. You’re constantly treading the line between complex concepts and simple terms, and that’s quite hard to do. We wanted it to be an accessible, engaging story. It’s a complex message to get across and you want to simplify it rather than making it simplistic. But if it’s a story, people get curious and it stimulates the imagination. You put down your defences around the problem and allow yourself to explore.

One of the things we loved about fables is that they’re so accessible. They take a complex message and, relatively indirectly, convey it to the reader.

Why did you choose the story to be about a Barista and a Young Manager, and the journey he goes on?

Pete: We wanted something that could connect with everyday life. We don’t give the Young Manager a name so anyone can identify with him. There are some hidden messages in the story as well. For instance, the group of companies in the converted power station where the story is set is called ‘The Collective’. We’ve always believed in the power of people coming together to create change. And, in a busy working life you just get a few moments in your day to reflect. This might happen when you’re queuing for a coffee. A barista might help you disconnect from your distractions and reconnect with yourself for a moment. We wanted it to feel modern, relevant and familiar.

Mark: The Barista represents those little moments in the day where people actually do take to disconnect a little bit from the fast paced world around them. We’re constantly surrounded by technology, emails, phone calls and so on. But people do usually prioritise their coffee, and that gives them a little window for a human connection.

Pete: This is important. When we get stuck we often feel like we need some big, miraculous solution to our problem, while what we actually need is some common sense, everyday wisdom. Perhaps someone behind a coffee counter could give this to us.

Which aspect of your method do people struggle the most with?

Pete: The gold nugget metaphor. It’s about finding exceptions to problems you feel are always there. We are so quick to generalise, in our language and due to our biases and the limitations of our minds. It’s when you assume the problem occurs all the time, in every context, no matter what you’ve done, even though this isn’t true. This is what holds you stuck. You need to get curious about the times the problem does not occur, what the circumstances are when it does happens, and see the problem as a special and unique occurrence. This is a fundamentally different way of viewing the world.

Mark: I agree this is what people struggling with the most, because you’re asking them ‘when is this problem not a problem?’ We tend to use emotive language and general statements like ‘always’ and ‘never’, and people struggle to accept that it might not be a problem literally all the time. So for instance, when someone says to you that their colleague is never on message during meetings, this can’t be completely true; there must be moments when they are. People are so fixed on looking for the problem after they’ve defined it, finding it just reinforces the idea it’s there all the time.

Pete: This can be a pride issue as well. For example, if you feel like you argue with your partner constantly, and you feel like you’ve tried everything to solve this with no results, you might be stubbornly holding on to this idea that it’s a constant struggle rather than a circumstantial one. Ask yourself, do you argue in the middle of the night? Probably not, because you’ll be asleep. During the day you’re both likely to be at work so you can’t argue then. If you go through this process of elimination, as silly as it may seem, you may find the problem only with a very specific recipe, for instance after work in the kitchen when you’re cooking together.

Mark: And that changes the frame of the issue from it being a ‘relationship problem’, which is huge, to a ‘we argue in the kitchen after work problem’, which is a lot easier to solve.

Which fables have helped you and shaped your thinking?

Pete: We absolutely loved Who Moved My Cheese?. Spencer Johnson nailed the power of simplicity. You could read that book and think it’s the most ridiculously simple story about mice in a maze, but if you really listen to what it has to say it changes into something profound about accepting change. It’s very short and we love that it conveys something so complex through something simple. It’s accessible and easily applicable. You don’t need someone to interpret it for you, or explain the metaphor.

Mark: It also captured the spirit of a time where we learned that change is inevitable. We won’t have periods of time anymore where everything is stable. The working world is now dynamic and constantly shifting and this book captured that. And we find it very interesting that we have clients who tell us that book changed their lives, even though it takes barely an hour to read, and the infinite different interpretations they have. It frees them up to see things differently. And it exemplifies one thing we love about fables, that throughout reading them, you always get the sense you’re not the only person with this problem. Other people have been in the pig pen, other people have been in the maze looking for cheese.

Sign up to the Penguin Connect newsletter

By signing up, I confirm that I'm over 16. To find out what personal data we collect and how we use it, please visit our Privacy Policy