- Home |

- Search Results |

- Kevin O’Rourke on Brexit: Britain has always been ambivalent about Europe

Kevin O’Rourke on Brexit: Britain has always been ambivalent about Europe

In order to understand the present, we need to turn to the past. Here, Kevin O'Rourke, one of the leading economic historians of his generation, explains Brexit: the culmination of events that have been unfolding for decades, with its historical roots stretching back well beyond that.

What explains Brexit? The question will keep many academics happily employed for years.

Britain’s relationship with Europe was always an ambivalent one, it had always looked towards its imperial past and its relationship with America. It initially tried to sabotage European integration, and when the government eventually decided that entry was in the UK’s best interests it did so in a less than whole-hearted fashion. The British traditionally valued the economic opportunities afforded by Europe, but were much less enthusiastic about the supranational ambitions of the European Communities.

And when the European Communities made way for the European Union, a Conservative Party civil war erupted: for many within the party this was a dilution of sovereignty too far. Add to this the ambivalence of a small but influential section of the Labour Party, and in particular its leader since 2015, as well as the rise of UKIP, and Brexit was unsurprising.

But Brexit was not inevitable: Leave only won by a small majority. Thirty-three million six hundred thousand people voted in the referendum. If just 635,000 of these had voted to Remain rather than Leave I would not be writing this.

People often assume that economic explanations of voting behaviour must imply rational behaviour, but that isn’t so.

So is Brexit focused solely on the United Kingdom or is it part of a bigger story? As we know, 2016 was marked not only by the UK referendum but also by the election of Donald Trump in the United States. The following year saw an uncomfortably strong showing for the French National Front, which made it into the second round of the presidential election, and the arrival to power (albeit as part of a coalition) of the far-right FPÖ (Freedom Party of Austria) in Vienna. In 2018 a populist government was elected in Italy. There are strong populist parties elsewhere in Western Europe, and populist governments in Hungary and Poland. When you see common trends of this sort in many countries a common explanation seems in order.

What form might such a common explanation take? There is a raging debate today in both Britain and the United States regarding whether Brexit and Trump reflect ‘economics’ or ‘culture’. For some, both phenomena are the product of globalisation, or technological change, or other impersonal economic forces that are damaging vulnerable communities. For others, they are the product of racism, xenophobia, nationalism and other forms of extreme cultural conservatism. The question of whether economics or culture explains these two watershed political events is in many respects an ideological one. Some on the left are reluctant to admit that either Brexit or Trump might have an economic explanation, for fear of justifying those who voted for them. Some on the right are happy to parade their solidarity with those who have been left behind, and to portray the political upsets of 2016 as a victory for the common man, although neither the UK Conservatives nor the US Republicans have traditionally distinguished themselves by their concern for the poor.

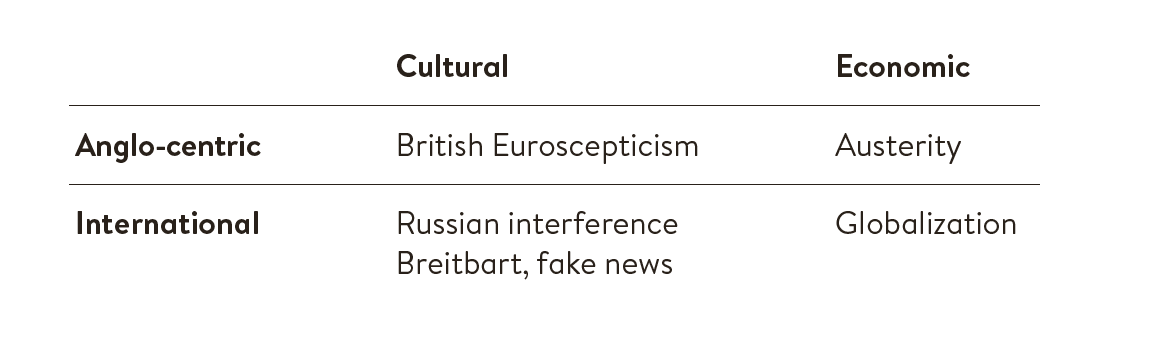

Schematically, one could envisage a catalogue of structural explanations as in the table below, distinguished by whether they are Anglo-centric or international, and economic or cultural. The Anglo-centric and cultural explanation is one possibility, listed here in the top left-hand cell of the matrix; the alternative argument that both Brexit and Trump represented a revolt against globalisation is listed in the bottom right-hand cell (it is both international and economic). One could imagine explanations that are both international and cultural– the systematic use of the Internet by Russia to destabilise Western democracies, the spread of fake news by far-right organisations such as Breitbart News, international networks of populist politicians and pundits, or the abuse of personal data by companies such as Cambridge Analytica (which worked for both the Trump Campaign and Leave.EU). And there are explanations that are both British and economic, such as those emphasising the role of the UK government’s radical austerity drive under David Cameron and his Chancellor George Osborne.

Finally, there is a distinction that matters greatly to economists and a certain sort of political scientist– were voters rational or not? If a voter in the American rustbelt supported Donald Trump because he or she was suffering as a result of international trade, and thought that Donald Trump would be protectionist, then you could view their vote as a rational one. Alternatively, you could view both Donald Trump’s supporters and those who voted in favour of Brexit as having been fooled by unscrupulous politicians. Economists tend to believe that people behave in their own best interests, and in ordinary life it usually makes sense to assume that those with whom you are dealing are going to do what’s best for them. But just because something is usually true doesn’t mean that it always is, and in any event if it is costly to acquire information about the costs and benefits of European integration or globalisation then a rational person may decide to remain ignorant.

People often assume that economic explanations of voting behaviour must imply rational behaviour, but that isn’t so. To be sure, our hypothetical rustbelt voter is voting in his or her own best economic interests, which is what economists tend to define as ‘rational’ behaviour. But what about a hypothetical British voter supporting Brexit because of Conservative Party austerity? It would be difficult to argue that this wasn’t an economic reason to vote for Brexit, but it would hardly be a rational one, given that Osborne’s austerity policies had little or nothing to do with Europe. The UK is not a member of European Monetary Union, nor is it bound by the European Fiscal Compact, nor are the avoidance of excessive deficits and debt and the associated numerical fiscal rules mandated by the Stability and Growth Pact directly binding upon it. George Osborne’s austerity was Made in Britain. If our hypothetical voter supported Brexit because he was unhappy with austerity, he was aiming at the wrong target.

If I were teaching Brexit in 50 years’ time, this is probably how I would introduce the subject. My students would then write essays debating whether the causes of Brexit were cultural or economic, British or international, rational or irrational. These distinctions make pedagogical sense, and they help in understanding what is a complex social phenomenon. But my guess is that, having gone through all the arguments, and assessed all the empirical evidence, and read the authoritative histories of Brexit that would have been written at that point, the conclusion would be that Brexit was complicated, and that all of the reasons mentioned above mattered. Because that is nearly always the conclusion that you reach in questions such as this one.

This is an extract from A Short History of Brexit by Kevin O'Rourke, published on 31 January 2019.