- Home |

- Search Results |

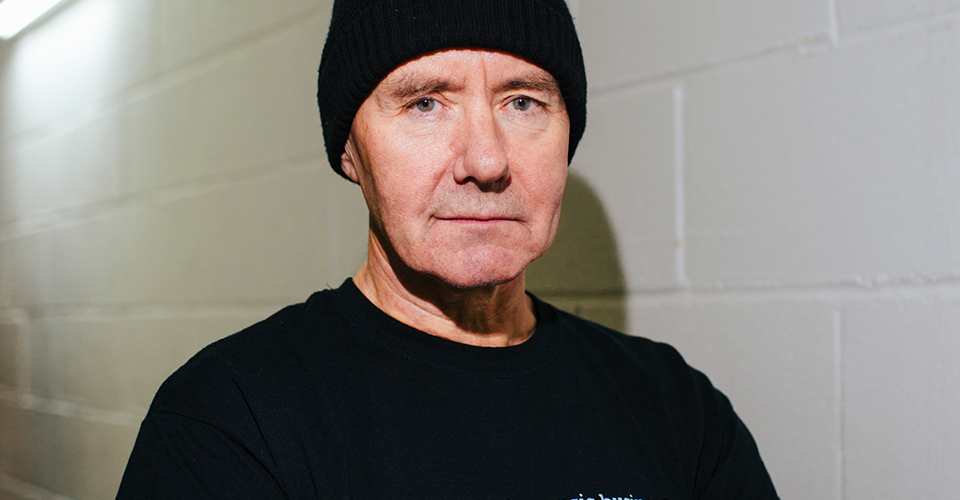

- Irvine Welsh: I knew one of these guys had to die

A lot has changed since Irvine Welsh’s genre-bending, era-defining cult classic debut was published. Trainspotting was released in 1993 and followed the exploits of a group of young men from Leith, Edinburgh. Fast forward a few decades, via several other novels about the characters, and you arrive at Dead Men’s Trousers, which follows Begbie, Renton, Spud and Sick Boy against a backdrop of Brexit and Scottish independence as they grapple with new loyalties, old grudges and an ill-advised detour into black market organ harvesting.

Welsh hadn’t been planning on checking back in on his antiheroes so soon: “You think you’re done with them, and then they come back and you want to find out what they’re up to - you just get a bit curious.” Working on Trainspotting 2, a loose adaptation of Welsh’s 2002 novel Porno, with the same director and same cast as the original film, was the catalyst: “It really embedded the characters back in my consciousness again, it made me think where we could go from there.”

Dead Men’s Trousers checks back in on the four former friends as their lives have taken disparate turns; Renton is working as a successful jet-setting DJ manager, Sick Boy is dealing with accidentally breaking up his sister and her husband, Spud is desperate for work, and Begbie seems to have found his zen, living in California with his wife and two daughters, working as a successful artist. Of course nothing is quite as it seems, and everything starts to derail once their orbits collide:

“I like the idea that everybody is in an existential crisis, they’re not really sure of the world around them, all the certainties of this world are breaking down and moving into a post-industrialist, post-capitalist world. I think a lot of people who are superficially successful are feeling that they get to a certain point and think: why am I doing this?”

For Welsh, this mirrors the existential crisis the real world is going through: “All the old certainties, the old divisions of labour, of gender, of class, are changing; it’s affecting the whole of humanity and manifesting itself in different ways; the Me Too movement, Black Lives Matter, Catalan independence, the fragmentation of the old imperialist states; the old hierarchical structures are dissolving. We’re asking these big questions now but characters like Spud were asking them back in the 80s. People weren’t just sitting back thinking ‘Ah, I’m fucking depressed, I’m on the dole, I’m shooting up smack,’ they were thinking about what it’s all about, am I going to work again, what am I going to do with my life. When you had the move from medievalism to capitalism you had the Black Death; I think drugs are the transitional plague now as we move from capitalism into conceptualism.”

The book alternates between the four men’s perspectives and they are familiar but marked by the world they now live in. For Welsh, it wasn’t hard to find their voices again: “They’re so much a part of me, you just get back into that rhythm. People are like music, they all have a different beat, a different rhythm. When you see a group of friends, they have a flow to them. When you see people in a relationship, they have a kind of beat. I think that when relationships evolve and the beats don’t sync up properly, that’s where a lot of problems between people come from. There is an internal rhythm people have and annoyances in life are about having our rhythms disrupted or distorted.”

The rhythms of these men’s lives are well and truly distorted when Spud takes on a dubious role in a dodgy black market kidney transplant deal. Everything spirals out of control, and their lives are thrown together once more. The fact that one of the men does not survive the book is not a spoiler: “I thought: one of these guys has got to die, I can’t hold on to them all. In the first draft I toyed with the idea of every one of them at one point. But it’s not difficult to me emotionally - it’s an exercise, a tool in telling a story. There might be a time in the future when I look back and feel sad, but I’ve lost so many people over the years, I’ve lost really good friends, a lot of them taken before their time. When you have the reality of that, you’re not really that concerned about fictional characters.”

We’re asking big questions now, but people like Spud were asking them in the 80s. They weren’t just sitting thinking ‘I’m fucking depressed, I’m on the dole, I’m shooting up smack.

Welsh won’t be drawn on if he has a favourite character to write, though: “You have to like them all. Every character you writer. Like is maybe the wrong word, but you have to be able to empathise with them all, put yourself in their position and look at it through their eyes. I’m drawn towards more dramatic characters, like Begbie and Sick Boy, and more complex ones like Renton, but good guys are nice to write as well because you get a bit of respite.”

There have always been comparisons between Welsh and his characters, which he sees as “kind of inevitable, but I don’t lead an interesting enough life for every book to have an autobiographical edge”.

For Welsh, the characters represent something more complex than himself or people he knows: “To me, the characters are different emotional states; I build them from there. You’re always thinking about what story you want to tell, and who the characters are that you’re telling it with. You’re using elements of yourself, but there is always a conscious act of composition going on. Everything is composed and constructed and takes a lot of time to get right. You try to capture the sights and sounds and moods and behaviours; you just keep trying to get better at it.”

For example, he sees Begbie’s transition to apparent calmness as a narrative necessity: “It’s the only way he becomes dramatically viable. If you kept him on the same trajectory he’d be dead or in prison; he has to be reinvented. He still has all this ultra-violence, but he’s in control of himself, so in some ways he’s a lot more dangerous than he was. He’s a poster boy for white male rage, railing against redundancy. He’s taken on a kind of iconic status - I get a lot of fans saying he’s brilliant and I’m like, ‘You’re missing the bigger picture a wee bit!’

“But it’s the thing about fiction; people take from it what they take from it. You can’t really tell people how to read a book, or how to enjoy a book. Everything you do, every movie you see, every book you read, you filter it through your own mind and experience.”

In many ways Dead Men’s Trousers feels like an ending. One character has died, and there’s a level of resolution for some of the other characters: “I wanted it to be an ending of sorts because I wanted them to be finished as a gang. There’s no way these guys will all be together in the same space again. I felt like I was almost pushing it a bit with this one. I mean killing one of them off makes it easier, and I think I could see them coming into each other’s orbits, or one of them cropping up in different stories. I like the idea of one of Begbie’s young girls being a psychopath - a female Begbie but raised in a very affluent California liberal household - it’s an interesting construct. There’s a lot of things to ponder. But in a way it’s not up to me,” Welsh says. “It’s more whether they’ve finished with me.”