- Home |

- Search Results |

- Moving World War One poetry to mark Remembrance Day

There were months of fighting in horrific, inhuman conditions. Over half a million British and French dead; all for what are usually deemed relatively small gains. The Battle of the Somme has come to stand for the horror and futility of the First World War.

These heroic men had their lives changed immeasurably by WW1. Documented by their words, they have left us a poignant reminder of the atrocities of the event, and their personal sacrifices.

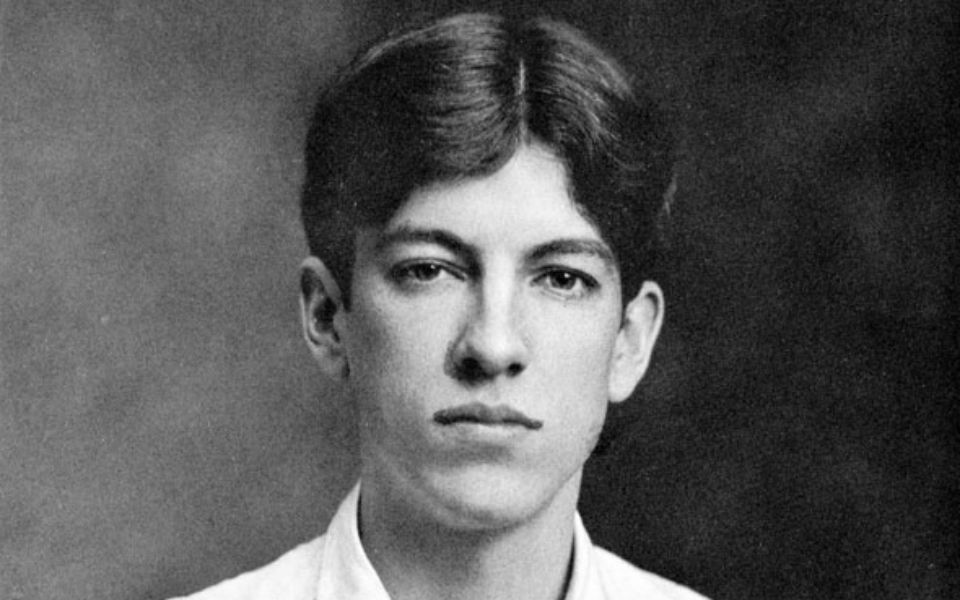

‘Anthem for Doomed Youth’ by Wilfred Owen

Owen fought at the Somme and was admitted to the Craiglockhart War Hospital in Edinburgh in 1917 after suffering PTSD (diagnosed as shell shock at the time) where he met Siegfried Sassoon, who helped him channel his war flashbacks into poetry. He returned to fight and was killed in action a week before the war ended, in November 1918.

What passing-bells for these who die as cattle?

– Only the monstrous anger of the guns.

Only the stuttering rifles’ rapid rattle

Can patter out their hasty orisons.

No mockeries now for them; no prayers nor bells;

Nor any voice of mourning save the choirs, –

The shrill, demented choirs of wailing shells;

And bugles calling for them from sad shires.

What candles may be held to speed them all?

Not in the hands of boys but in their eyes

Shall shine the holy glimmers of goodbyes.

The pallor of girls’ brows shall be their pall;

Their flowers the tenderness of patient minds,

And each slow dusk a drawing-down of blinds.

'The Kiss' by Siegfried Sassoon

Sassoon was decorated for bravery on the Western Front and was nicknamed 'Mad Jack' by his men for his near-suicidal exploits. In 1917, he rebelled against the conduct of the war in a letter to his commanding officer and was sent to Craiglockhart War Hospital, where he was officially treated for PTSD. He returned to the Front but was wounded in 1918 when he was shot in the head by a fellow British soldier who had mistaken him for a German. He survived. Sassoon wrote ‘The Kiss’ in training shortly before the Battle of the Somme.

To these I turn, in these I trust;

Brother Lead and Sister Steel.

To his blind power I make appeal;

I guard her beauty clean from rust.

He spins and burns and loves the air,

And splits a skull to win my praise;

But up the nobly marching days

She glitters naked, cold and fair.

Sweet Sister, grant your soldier this;

That in good fury he may feel

The body where he sets his heel

Quail from your downward darting kiss.

'On Somme' by Ivor Gurney

Gurney was a poet, an accomplished musician and a composer. He wrote hundreds of poems and more than 300 songs. He survived the war but was sectioned in a mental hospital in 1922, having suffered periods of mental illness that predated his service. He died of tuberculosis at the City of London Mental Hospital in 1937.

Suddenly into the still air burst thudding

And thudding, and cold fear possessed me all,

On the gray slopes there, where Winter in sullen brooding

Hung between height and depth of the ugly fall

Of Heaven to earth; and the thudding was illness’ own.

But still a hope I kept that were we there going over,

I, in the line, I should not fail, but take recover

From others’ courage, and not as coward be known.

No flame we saw, the noise and the dread alone

Was battle to us; men were enduring there such

And such things, in wire tangled, to shatters blown.

Courage kept, but ready to vanish at first touch.

Fear, but just held. Poets were luckier once

In the hot fray swallowed and some magnificence.

‘I have a rendezvous with Death’ by Alan Seeger

The American poet volunteered to fight for the French Foreign Legion in 1914 and died at the Battle of the Somme on the fourth of July, 1916. Seeger was reported to have been cheering on the second wave of advance as he lay dying from his wounds. ‘I have a rendezvous with Death’ was published posthumously.

I have a rendezvous with Death

At some disputed barricade,

When Spring comes back with rustling shade

And apple-blossoms fill the air –

I have a rendezvous with Death

When Spring brings back blue days and fair.

It may be he shall take my hand

And lead me into his dark land

And close my eyes and quench my breath –

It may be I shall pass him still.

I have a rendezvous with Death

On some scarred slope of battered hill,

When Spring comes round again this year

And the first meadow-flowers appear.

God knows ’twere better to be deep

Pillowed in silk and scented down,

Where Love throbs out in blissful sleep,

Pulse nigh to pulse, and breath to breath,

Where hushed awakenings are dear . . .

But I’ve a rendezvous with Death

At midnight in some flaming town,

When Spring trips north again this year,

And I to my pledged word am true,

I shall not fail that rendezvous.

‘Two Fusiliers' by Robert Graves

The famous poet, novelist and critic fought at the Battle of the Somme and was so badly wounded he was reported to have died. Graves was friends with Sassoon and, following Sasoon's anti-War statement, persuaded military authorities that his friend was suffering from PTSD. He lived until 1985.

And have we done with War at last?

Well, we’ve been lucky devils both,

And there’s no need of pledge or oath

To bind our lovely friendship fast,

By firmer stuff

Close bound enough.

By wire and wood and stake we’re bound,

By Fricourt and by Festubert,

By whipping rain, by the sun’s glare,

By all the misery and loud sound,

By a Spring day,

By Picard clay.

Show me the two so closely bound

As we, by the wet bond of blood,

By friendship, blossoming from mud,

By Death: we faced him, and we found

Beauty in Death,

In dead men breath.

These poems are collated in The Penguin Book of First World War Poetry.